As explained in our earlier posts, we were inexperienced, but wanted to do something.

So, with all the noble intentions, some euphoric planning and thinking, we finally decided to convert the building in to a tourism unit along the lines of the Boarding Houses of Europe. Architects were consulted, plans were drawn up, approximate costs were worked out, and we found the money! Now all that was required was getting the labour to start renovations.

Or that’s what we thought!

Our local panchayat told us we may to get permission to renovate as our heritage building fell in the Special Area Development Authority. We scrambled to Dharamshala to meet with the Town and Country Planning. They gave us forms and formats to fill and suggested we don’t carry out any changes till they cleared it. We filled the forms, submitted all the documents. Then followed a series of meetings, clarifications, more documents and then silence.

Several months later we got a letter stating that we did not fall under the purview of SADA and hence no permission was needed to renovate our building. We heaved a sigh of relief, and moved on to the next step – renovation. Being responsible citizens we thought we will use local labour and craftsmen.

We thought wrong! For starters, they would not come when you want them to. And when they did come, they would take two tea breaks, two beedi breaks, one lunch break, come at 9 and leave by 5, and they wanted to be paid city rates. And while they worked, if anything happened in the village or nearby, they would just leave.

We hadn’t realised that our fellow villagers were a contented lot, happy to work when they wanted to, not when we wanted them to!

Then, we had not factored the villagers right to protest.

And protest they did, From questioning our credentials, to what we were doing, to claiming we were encroaching on public property and to generally protesting! One of them actually went to court to get a stay order but fortunately approached a lawyer known to us. The lawyer was able to convince them of our bonafides, so they relented. Several confabulations later, mixed with a few threats, a few homilies and a few contributions to local causes, the stage was cleared for us to start the process of renovation without any further impediments.

But wait! There were permissions from various departments to be obtained – structure, Electrical, fire, water, pollution, FSSAI, tourism etc. Some were required before we started, some when we finished It was a classic catch 22 situation, you couldn’t do one without the other.

We decided it was better to ask for forgiveness rather than asking for permission, and started in right earnest.

We requestioned a team of contractors from Delhi.

The first task was to clean the place. It took 4 people 15 days and 45 trolleys loads to clean out the garbage including several decades of human and animal fermentation!

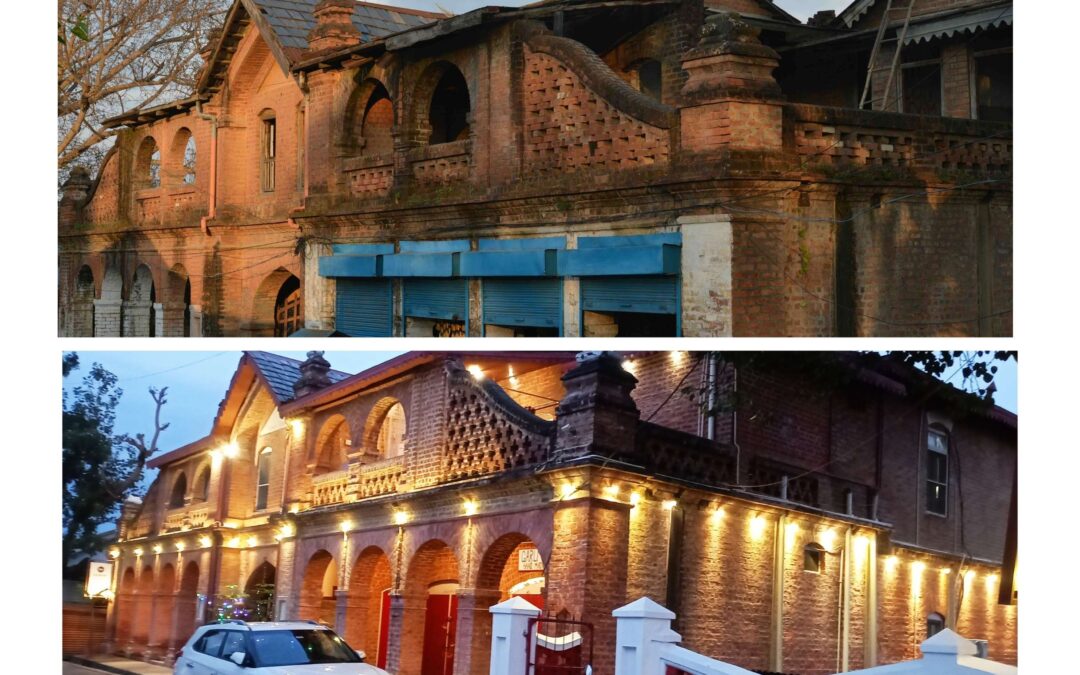

The brick façade was filthy, and we simply did not want to paint over the building, so we decided to wash and scrape the grime off the bricks. 30,000 litres of water, 250 Kgs of washing powder, 75 iron brushes, 18 people and 15 months later, she began to smile.

Unfortunately the brickwork in the rooms was etched with graffiti, so we had no choice but to cover the walls with plaster, and paint them over. The doors were warped. They had to be replaced.

Then came the issue of modern amenities – Where do we put the bathrooms? There wasn’t enough place inside the rooms. If we built the bathrooms externally, then not only would we be ruining the outer façade, but also increasing the cost of renovation manifold. We decided to build common bathrooms and toilets.

Many people turn away even today, when they hear of common bathrooms, even though they acknowledge its cleanliness and hygiene. It’s a decision we took, and stand by it.

As we progressed, we encountered many interesting episodes, but one particular incident is etched in memory.

There was no sewage system in the village, so we had to make our own septic tank / soak pit. The location we chose was infested with a clump of bamboo plants. JCBs were not so common in those days, so we had to rely on manual labour to clear the bamboo, and dig the pit to our specifications.

One enterprising group of 3 villagers approached us and offered to do everything on a fix price basis. We asked them how long it would take, and they said a week. We agreed on a price, gave them the advance. At the advice of the local person, I also gifted them with a bottle of Royal Stag as an anticipatory thank you and left.

Two days later we got an SOS call from our neighbour saying a cow had fallen into our pit. Puzzled, we rushed over to find a very annoyed cow mooing at us with displeasure from a deep pit where once a bamboo clump stood. We requestioned some people and some rope to pull the cow out. If only we could have recorded that incident of a belligerent cow being hoisted up by a gang of people, it would have become viral!

With the indignant cow duly despatched, and surprised at the sudden appearance of the pit, we called for the 3 people only to learn they were “indisposed”. Apparently they were so thrilled with my gift of whiskey that they called a few more friends, bought some more alcohol, spent the full day and night drinking and working, dug a pit larger than we wanted, and celebrated by draining the bottle I had given them!

Coming back, we still had to electrify the place. Lights inside the room were not an issue, it was the outside that was a challenge. We wanted the glory of the building to show up at night, and in those days we did not have too many choices. The existing lighting devices were expensive, and would consume an enormous amount of electricity. We estimated around 250 tube lights internally which would also add to electricity costs.

LEDS lights were just becoming popular, but they were expensive. So we decided to build our own LED luminaries! Several trips to Chandni chowk, and lots of experiments later, we managed to design our own lighting system. We requisitioned a local carpenter to build the boxes, the local glass dealer to cut and etch the glasses, two lads to do the soldering and wiring, and voila, we had a lighting solution not seen anywhere else at that time!

Not only did we achieve our lighting objective, but we also saved massively on lighting costs. Now every night she is lit up so that all passers-by can marvel at her glory

So now we had the plumbing, the electricals and the sewage in place. But what should she look like? We chose the theme of Red-White-Grey to showcase the building. Painters were called in, and the photographs say it all.

Then came the furniture. In a tourism unit, It would get used, and maybe abused. With humidity levels at 60% plus, and lack of sufficient seasoned wood, we decided to fabricate our own beds and room accessories. A bemused welder built the 25 beds, 30 towel racks, 40 luggage benches and 15 odd tables which were then painted red to harmonise with the design theme. We called a mattress person to make us 30 cotton filled mattress, and 40 cotton filled quilts.

We had some really old, solid furniture at home, which we used to furnish the dining hall and lounge. Some of the items are more than 150 years old!

Finally, several trips to the crockery store, the fabric store, the hardware store and the linen store later, we managed to furnish, drape, and equip Naurang Yatri Niwas and open it for the public.

It took us two years to ensure that we protected the glory of the building, and seamlessly build in all the modern conveniences so that out guests could experience staying in a 100 year old building, but still be comfortable

Today it is a matter of pride for us when any visitor steps into our building for the first time, their normal reaction is “WOW”!

And that reaction, alone, friends, is simply worth it